Artificial Intelligence

We Are Biological Machines

Programmed By Our Caregivers

- Between Clinical Psychology & Engineering -

Artificial Intelligence

The MAPP puts relationships – and especially the close ones – at the center of psychological phenomena but, at the same time, adopts an engineering approach. Its description and explanation of mental functioning are compliant with the architecture of the mind, which is seen as both an information processor and control system.

As a result, the theory is particularly suitable for computational implementation. Such an application has been realized by building an agent-based model of the attachment interactions between a child and their caregiver with respect to 3 dimensions: avoidance, ambivalence, and phobicity.

The resulting patterns of behavior – simply outlined by two dots on a screen – powerfully convey the idea of a personality trait. This application is the first step towards the creation of AI capable of attaching and giving care.

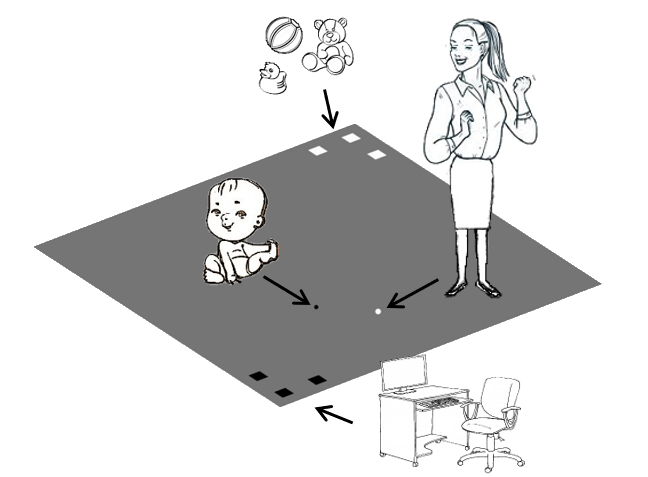

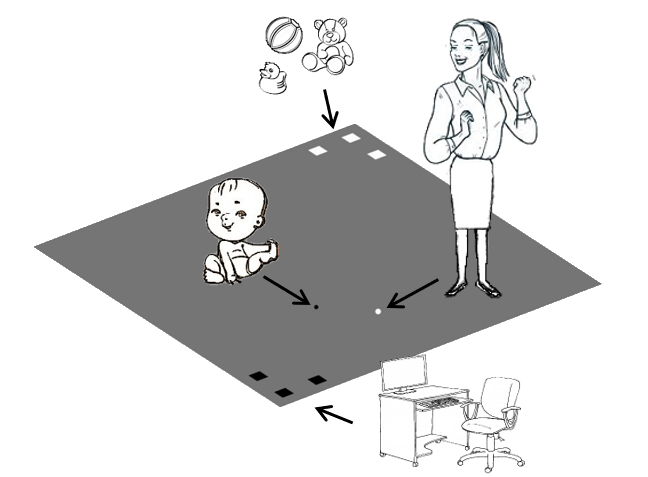

In this basic implementation of attachment interactions between a child and their mother, we imagine the two while interacting in a kind of large squared room, at the corners of which some objects are placed.

The two protagonists are simply represented by dots, but they can express their intrinsic motivations either to receive care – the child – or to provide it – the mother – by approaching the other. When they are not driven by such motivations, they can explore the room and the objects they are interested in.

This way, we can endow an artificial baby with the essential quality of our personality traits. Here, we do that for avoidance, ambivalence, and phobicity.

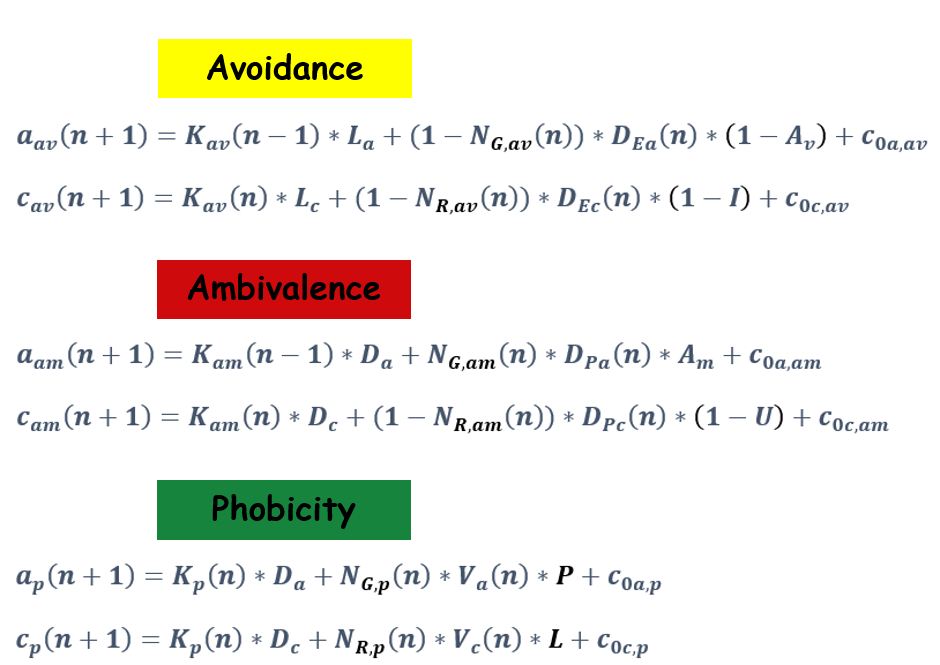

1. The Equations of Attachment

The MAPP allows us to translate the clinical psychological concepts into mathematical equations.

This opens up exciting prospects for the further understanding of human personality and relationships but also for the creation of AI that integrates fundamentally human qualities such as looking for care and offering it.

The next generations of baby robots will attach to us and the adult ones will connect emotionally to us and provide care when we need it.

2. Avoidant Child-Mother Interactions

The child who is taken care of by an insensitive caregiver is expected to become avoidant.

The caregiver is not sensitive to the emotional needs of their child – at least, to the extent that the child would feel necessary. As a result, the child limits their requests for emotional care and becomes emotionally detached and over-independent of the caregiver.

Note. In the clip, the child is a black dot, which turns yellow every time they ask for care. The caregiver is a white dot, which turns into a yellow star every time they provide care. In this case, care is of ‘avoidant kind – i.e. emotional connection, which we can call love.

The clip shows how an extremely avoidant child-mother dyad tends to behave: they are very independent of each other.

The child does not ask to be cared for – they do not approach – and the caregiver does not offer such care – they do not approach either. On the other hand, they both engage in other activities – they explore.

This behavioral pattern of the child visually emphasizes their predominant avoidant personality trait. Importantly, such behavioral pattern and personality trait match those of the caregiver.

Note. In the clip, the child is a black dot, which turns yellow every time they ask for care. The caregiver is a white dot, which turns into a yellow star every time they provide care. In this case, care is of ‘avoidant kind – i.e. emotional connection, which we can call love.

The clip shows how an extremely ambivalent child-mother dyad tends to behave: the child is very dependent on the caregiver and preoccupied to receive their physical attendance, while the caregiver is mostly engaged in other activities.

The child insists on asking to be cared for – they continuously approach – and the caregiver does not offer such care – they do not approach. On the other hand, the caregiver is very busy with their own business – they explore. The child ends up spending their time chasing the caregiver.

This behavioral pattern of the child visually emphasizes their predominant ambivalent personality trait. Importantly, such behavioral pattern and personality trait match those of the caregiver.

Note. In the clip, the child is a black dot, which turns red every time they ask for care. The caregiver is a white dot, which turns into a red star every time they provide care. In this case, care is of ‘ambivalent kind – i.e. reliability of physical attendance.

3. Ambivalent Child-Mother Interactions

The child who is taken care of by an unresponsive caregiver is expected to become ambivalent.

The caregiver is not responsive to their child’s needs of physical attendance – at least, to the extent that the child would feel necessary. As a result, the child intensifies their requests for physical attendance and becomes over-emotional and dependent on the caregiver.

Note. In the clip, the child is a black dot, which turns red every time they ask for care. The caregiver is a white dot, which turns into a red star every time they provide care. In this case, care is of ‘ambivalent kind – i.e. reliability of physical attendance.

4. Phobic Child-Mother Interactions

The child who is taken care of by a limiting caregiver is expected to become phobic.

The caregiver limits the autonomous exploration of their child, thereby leaving such child’s need unmet – at least, to the extent that the child would feel necessary. As a result, the child feels vulnerable in the absence of the caregiver and intensifies their requests for physical protection from the caregiver.

Note. In the clip, the child is a black dot, which turns green every time they ask for care. The caregiver is a white dot, which turns into a green star every time they provide care. In this case, care is of ‘phobic kind’ – i.e. physical protection.

The clip shows how an extremely phobic child-mother dyad tends to behave: the child is very dependent on the caregiver and preoccupied to receive their physical protection, while the caregiver is likewise preoccupied to offer such protection.

The child insists on asking to be protected – they continuously approach – and the caregiver offers such protection – they also approach. The dyad ends up spending their time close to each other. Interestingly, their movements mostly take place around the objects of interest for the caregiver – who drives the interaction – thereby further limiting the child’s possibility of exploration.

This behavioral pattern of the child visually emphasizes their predominant phobic personality trait. Importantly, such behavioral pattern and personality trait match those of the caregiver.

Note. In the clip, the child is a black dot, which turns green every time they ask for care. The caregiver is a white dot, which turns into a green star every time they provide care. In this case, care is of ‘phobic kind’ – i.e. physical protection.

F.A.Q.

Artificial Intelligence

The MAPP conceptualizes the relationship between all the attachment variables and parameters. The formulated equations mathematically translate those relationships and animate the artificial child and caregiver. The computational results turn out to represent the essence of the real personality traits and attachment relationships, thereby further supporting the theory.

The dots are artificial autonomous agents driven by intrinsic motivations. In this case, the child-dot is driven by the motivations to attach and explore, while the mother-dot by those to give care and explore. Each agent’s motivations alternate to each other and can only be expressed by moving. Therefore, these agents are extreme abstractions of human beings in their living space. However, the resulting hyper-simplified system can reveal essential psychological properties and help us implement these properties into more complex artificial agents.

We are biological machines endowed by Evolution with multiple hard-wired drives: our intrinsic motivations. The MAPP identifies 19 of them divided into 3 evolutionary and psychological levels. At the bottom of this hierarchy are the individual motivations, such as eating or exploring for example. The central level is the relational one, to which attachment and caregiving belong. The top of the hierarchy is about more evolved motivations – such as the search for meaning and intersubjectivity – which are at the basis of our more elevated achievements. Transcendency is the highest objective we can aim at.

These computational simulations are abstract representations of the emotional detachment of an avoidant, the preoccupation for their relationship of an ambivalent, and the sense of vulnerability of a phobic. In real life, these characteristics can manifest themselves in many different – and often subtle – ways or even be latent for most of the time. The most immediate way to have an idea about their personality traits is to take the MAPP-T, which can offer valuable hints for further reflection. Talking with a psychologist is then the best way to go deeper into these matters towards self-development.

Yes, they can. The active dimensions/traits influence the activation of the motivational systems, which ultimately drive action. If we are avoidant, such knowledge easily becomes relevant and makes us activate a motivational system accordingly – the exploration one to inhibit attachment, for instance. If we are both avoidant and ambivalent, the two pieces of information do not become relevant simultaneously because the corresponding motivations – exploration and attachment, for example – would lead to incompatible actions. However, two dimensions can be supported by compatible actions – avoidance and obsessivity may both push toward exploration, for instance.